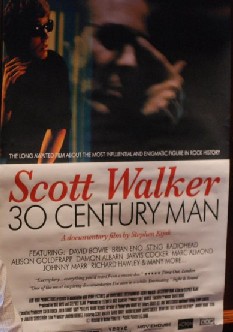

I've noticed something about the reviews I've read of Stephen Kijak's documentary

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man. Most of them end up being more about Walker's music than the film.

The intense focus on the music rather than the man isn't an accident, nor even a concession to Walker's legendary privacy, but a genuine reflection of Kijak's own focus. When I interviewed Kijak in Austin, the entire hour was spent talking about almost nothing

but the music. So don't see this film expecting an uber-cool alt/indie version of a VH-1 special.

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man isn't an industry "music bio."It's a film documenting what director Kijak called "the evolution of a songwriter over time."

David Bowie

From Scott Walker: 30 Century Man |

That evolution has covered a lot of territory, from his early years as a 60s UK boy band pop star, to his presence today as a composer of work so experimental and abstract it defies categorization. Scott Walker has crooned ballads to an orchestral accompaniment, and created percussion by thwacking a side of pork. He brought Belgian singer Jacque Brel into vogue with

Scott Walker Sings Jacques Brel and his still-iconic performances of

Mathilde and

Jackie. He entered the consciousness of a new generation of listeners with the stunning compilation

Boy Child: The Best of Scott Walker 1967-1970. He's influenced everyone from Lulu to

David Bowie (who executive produced and appears in the film) to Sting to the Smiths to Brian Eno to Marc Almond to Radiohead to Pulp (he produced

We Love Life, and Jarvis Cocker is all over the film) to Dot Allison, and dozens, even hundreds, of other musicians. And once you've seen it, there's something else anyone who has listened to alternative/indie music in the last forty years will quickly realize: Even if you didn't know Walker's name, you've been listening to musicians influenced by him all your life.

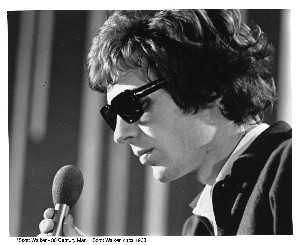

Scott Walker, c. 1968

From Scott Walker: 30 Century Man |

30 Century Man opens by casting Walker as a modern-day Orpheus, continually re-inventing and refining himself and his music. For listeners who find any part of Walker's musical evolution hard to follow -- be it is poppy past or his cutting edge present -- the next 90 minutes provide the context that makes it all make sense.

It would have been an easy trap for any filmmaker to fall into, to try to make a film that itself was as experimental as Walker's music. Kijak didn't fall, although he admits he was briefly tempted. Instead, he tells a beautifully-crafted, straightforward story, that will draw in anyone with an interest in music, and enchant Walker fans at the same time.

Director Stephen Kijak

photo by Clint Gilders - staff photographer |

"I thought I wanted to make a more elliptical, strange movie, but it just resisted it," he said. "And the music is such a strange evolution, it's such a unique story that the only way for it to really have an impact is to make it very linear, actually. Just to go from

"The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore" to

"Jesse", you know where he's screaming, 'I'm the only one left alive!' in this terrifying, really harrowing song. It has to be a straight line for the impact to really be felt."

Walker's public image isn't always a positive one. It's been said that he's difficult, that he's pretentious, and that he's completely insane. Anyone will know after seeing this film that he's none of those things. In his interview with Kijak, and in the studio scenes shot during the filming of his most recent album,

The Drift, he's unpretentious, down-to-earth, dryly funny -- even gentle.

"He's very serious and dedicated to what he's doing, but he"s not crazy," said Kijak, who had unprecedented access to Walker's studio during the recording of

The Drift. "At one point when we were filming a conversation with him and his colleague David Sefton. David said, "You know, Scott, most people expect you to be off twitching in a cave somewhere, and you're not. You're just a regular person who makes irregular records.'"

Brian Eno

From Scott Walker: 30 Century Man |

One of the most compelling features of the film for anyone interested in music is the lengthy interviews with musicians influenced by Walker. Not content to just let them talk, Kijak brought along examples of Walker's music, and then filmed the subjects of the interview listening to it. Watching Lulu's face while she listens to a cut from 1995's

Tilt is worth the price of admission alone - as is hearing Marc Almond (Soft Cell, Marc and the Mambas) go off on why he hates

Tilt. But the sheer volume and diversity of the artists who listen respectfully and rapturously to Walker's music - David Bowie, Brian Eno, Jarvis Cocker, Radiohead, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), Neil Hannon (The Divine Comedy), Alison Goldfrapp, Sting, Dot Allison, Simon Raymonde (Cocteau Twins), Richard Hawley, Rob Ellis, Johnny Marr, Gavin Friday, Peter Olliff, Angela Morley, Ute Lemper, Ed Bicknell, Evan Parker, Benjamin Biolay, Hector Zazou, Mo Foster, Phil Sheppard, Pete Walsh - is nearly an embarrassment of riches for anyone paying even cursory attention to alternative music over the last 30 years.

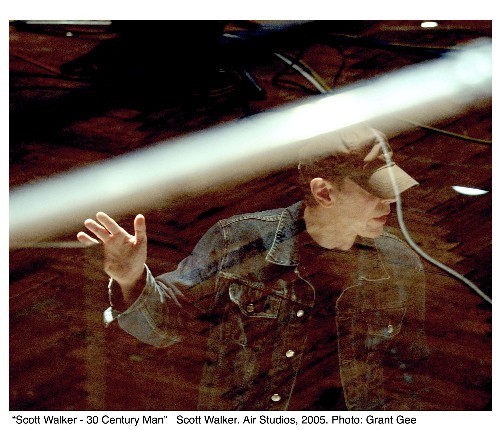

The film's most amazing moments, though, are the ones with Walker himself. Kijak films him in the studio working on

The Drift, including the infamous pork-whacking scene. Walker seems genuinely playful and happy, and completely oblivious to the presence of cameras. What was the first meeting like for Kijak?

"You see it in the film, actually," he said. "He comes in his little green coat and hat and they go, 'Hey, Scott!' That's the first time he walked in the studio. That's our first shot of him. And I'm behind him, shooting the B camera, and this guy walks in, in a green coat and I'm like, 'Get out of my way - Oh fuck, that's Scott Walker!' I drop the camera and I stand at attention because, you know, you don't want the first meeting to be camera in your face, you know how sensitive he is."

Scott Walker, Air Studio, 2005

Photo by Grant Gee |

Kijak continued, "This weird electricity shot through the room. It's like, 'He's here, he's here!' And I just dropped the camera and I'm thinking, I really hope the camera hasn't stopped rolling, or the battery just died, because that's our only shot. Thank God, it was rolling. Then he just went about his business and ignored us for about two and a half hours, while he just got down to work. We didn't want to get in his way, we're just flies on the wall, let's just watch him do it. I think later in the day it was just a handshake, 'Hi, how are you?' 'Very good, thank you.'"

So, how did Kijak get access to Walker, infamous for avoiding any form of publicity? Or as I asked him, how can you make a movie about someone who lives in a cave?

Kijak laughed. "Well, you know that's part of the challenge. You don't want to do a film about someone accessible. That's boring. It becomes a VH-1 special."

Of course,

30 Century Man couldn't be much further from a VH-1 special, thanks to its near-exclusive focus on the story of Scott Walker's music, rather than Scott Walker's life. That focus was one of the keys to how Kijak got Walker to participate in the making of the film. "He's making new music. I didn't want it to be a big retro trip. I wanted to say, "Look. I'm interested in your new music. I love

Tilt. I can't wait to hear what you do next. I look at you as an artist who's relevant now, who's moving forward. I'm going to do a very modern, very cinematic take on your music. Not on your life, on your music. On the evolution of a song writer through time.'"

Walker and his management also liked Kijak's outsider perspective. "I think what they liked was that it wasn't the establishment," he said. "It wasn't the BBC, it wasn't British, it was just someone coming and saying, "Let's do the Scott Walker story, without all the baggage of having known his fame in the 60s, the screaming girls and the Walker Brothers and all that.' So (Walker) says, "This is great. A young American looking into this story with a different, fresh perspective.' That appealed to them. And he's a crazy film buff, and he loved my last film. I sent him

Cinemania. And he somehow felt some complicity with these people, and liked the compassionate approach we took to a view of people on the fringe, to real outsiders. I think he felt like one of them in a way. Which is crazy, but he did. There's no one thing that made it happen, just a lot of work and a lot of careful planning and building a little team that would resonate with his creative world."

Scott Walker: 30 Century Man screens at Hot Docs: The Canadian International Documentary Festival in Toronto April 21"“22 and the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City on May 2, 3, and 5. For more information, visit www.scottwalkerfilm.com.